Salvado’s Story.

Salvado, Rosendo (1814–1900)

by Dom William

This article was published in Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 2, (MUP), 1967

Rosendo Salvado (1814-1900), Benedictine monk, missionary and author, was born on 1 March 1814 at Tuy, Spain, the son of Peter Salvado and his wife Francisca Rotea. The Salvado was a long-lived and musical family. Wealth at home favoured Salvado’s musical bent, but he pledged his vigour and talent to a higher cause. At 15 he entered the Benedictine abbey of St Martin at Compostela, was clothed in the habit on 24 July 1829, and took his three religious vows a year later.

In the new monk, music found more than a dilettante. The distinction won after a two-year course in organ-playing secured for him the post of first organist at St Martin’s in 1832. He was also an accomplished pianist and a composer. None of his music was printed but there are extant some of his sacred compositions written for his Western Australian Aboriginals and for convicts in Fremantle gaol, and a major work Fantasia, with variations and finale.

At 18 he added the study of liberal arts and philosophy to his duties as organist. The repose of the cloister was disturbed by the Spanish revolutionaries, who in 1835 decreed the closing of convents and the secularization of monks. Three years of patient waiting saw no end to the conflict, so in September 1838 he set out for Naples to be incorporated with the abbey of La Cava. There he was ordained priest in February 1839, and was instrumental in giving the abbey an organ which for mechanism, range and tone could rival the best in Europe.

This was the prelude to Salvado’s great epic. His philanthropy prompted him to flee his organ and its glory and to choose instead the retreat of a distant mission field. The Sydney mission under Bishop John Bede Polding was first proposed, but Dr John Brady’s consecration in Rome for the new see of Perth led to a change of mind. Salvado and his Benedictine confrère, Joseph Benedict Serra, were assigned to the bishop’s missionary party. They sailed from London in the Elizabeth and landed at Fremantle in January 1846.

Salvado was dedicated to what he believed the highest ideal in life, the reclaiming of souls. Monk first and apostle second, he wanted to use his talents on behalf of a raw colony where things had to be created. As an apostle he set up a system of Aboriginal education that surprised learned men, and as a monk he poured out his heart in prayer and applied the Benedictine Rule that made labour a duty of existence.

With Serra, whose main associate he was, he wound his way along a hundred miles (161 km) of bush track to a spot in the Victoria Plains, where on 1 March 1846 he established a mission for the training of Aboriginals; it was first named Central as the centre of proposed outlying Aboriginal missions, and later New Norcia, after Norcia, Italy, the birthplace of St Benedict. Hunger soon drove him back to Perth to give a one-man piano concert for which he was paid £1 from each of his audience of seventy music lovers. That saved his mission, but all through the formative years of New Norcia, 1846-67, he lived by ‘the sweat of his brow’. Dressed in dungarees, he looked nothing like the Catholic prelate of Protestant imagination. He drove his bullock cart, felled trees, ploughed, sowed and planted to turn the desert into a land rich in corn, wine and honey. Through his Rule he became a mystic, but a sociable one, fervent in seeking the Aboriginals, roaming with them and sharing their bush life. With a physique ‘enduring as marble’ he set hard standards that only Serra, out of a party of five, could share. But Serra too had to quit when he was appointed to the see of Port Victoria in 1848 and next year coadjutor in the diocese of Perth, and Salvado was left to shape anew the mission.

The change from nomadic to settled life started with the building of an abbey, round which the village came to be built. Here he gathered his Murara-Murara, Victoria Plains Aboriginals, and set about teaching them to work and to be Christians. By the method of inference he built ideas on ideas, his Western culture upon Aboriginal culture. Through their spears and boomerangs he taught the value and meaning of property and ownership. Soon his pupils were adept in husbandry, handicrafts and stockwork, many of them becoming first-class ploughmen, teamsters and farm workers. However, their poor physical strength and indolence hindered them from developing into responsible farmers.

According to Florence Nightingale, it was in Salvado’s school that ‘the grafting of civilizing habits on unreclaimed races was gradually accomplished’. The stone-age man had held his own against his surroundings; when the nimbleness, skill, endurance and rhythmical motion of the race were guided from the corroboree to the bat and ball, to brass and string music, the Murara-Murara became the heroes of the cricket field and of the music room. Salvado’s Aboriginal colony supplied Mivart with the strongest argument to refute his opponent Charles Darwin on ‘the essential bestiality of man’. It also gave to the world the first two black post-mistresses and telegraph operators, the one half-caste, the other full blood.

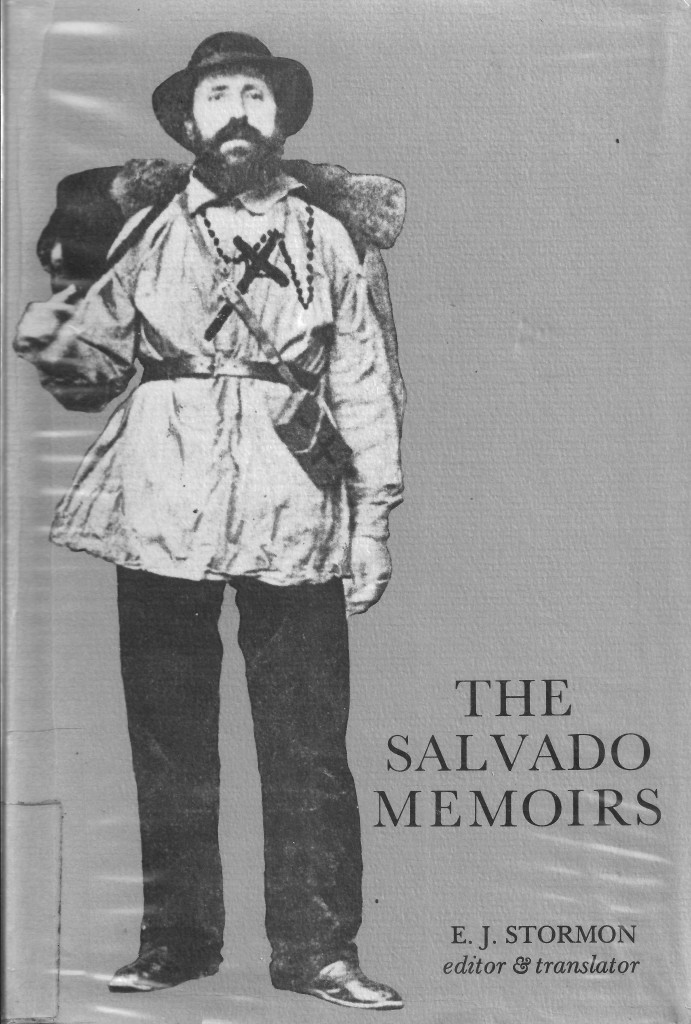

From the beginning Salvado believed that progress at New Norcia was checked by dependence on the bishop of Perth. Sent to Europe in 1849 to raise funds he also pressed the case for New Norcia’s home rule. In August he was consecrated bishop of Port Victoria in the Northern Territory. The closing of the garrison settlement deprived him of subjects before he left Italy and, while he waited in Naples for new orders from Rome, he wrote his Memorie Storiche dell’Australia Particolarmente della Missione Benedettina di Nuova Norcia (Rome, 1851); the first part was historical but the second and third dealt con amore with New Norcia and the Murara-Murara. This large work was published in Spanish in 1853, French in 1854, but never in English. Contemporary reviews judged it ‘a liberal book appealing to the mind and to the heart’.

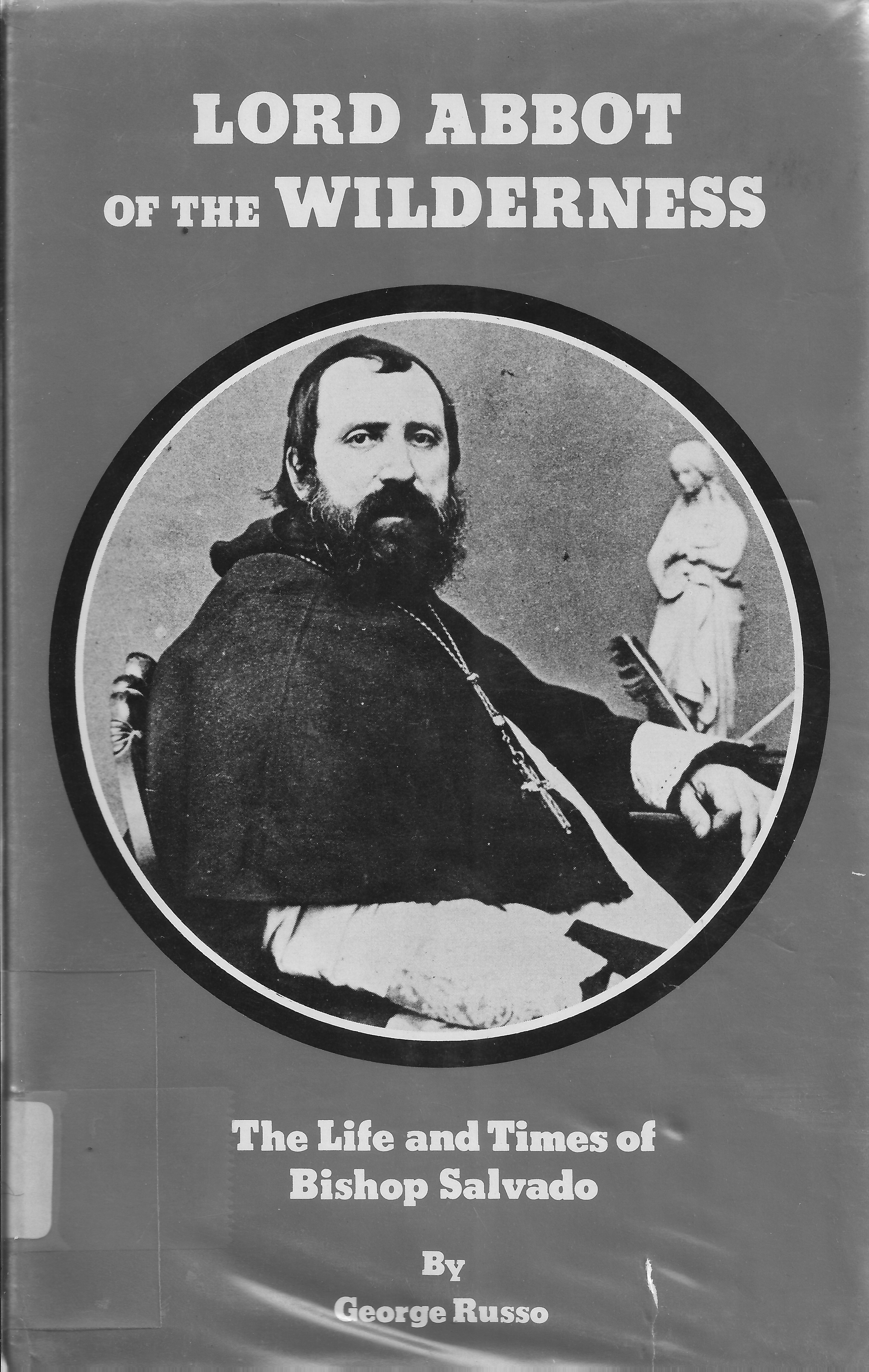

In 1853 Salvado was sent back to Western Australia. He administered the see of Perth while Bishop Serra was absent in Europe. Four years later he returned to New Norcia with renewed zeal to pursue his purposes for the mission of which he was named temporary administrator in 1859. But his prayer for home rule was not answered until 12 March 1867 when a papal decree gave Bishop Salvado of Port Victoria the additional title of Lord Abbot of New Norcia for life.

With greater freedom the mission entered a second period, 1867-1900, in which Salvado gave wider expression to the part of agriculture in monastic labour and took a leading part in shaping legislation on behalf of the Aboriginals. He and his monks had grown their daily bread by labour; now his journeys across a far-flung wild country looking for pastures and water and opening new tracks were to be as important for colonial expansion as for the mission. His efforts in seeking legal equality for whites and blacks in matters where the two races were equally concerned influenced the amendment in 1875 of the 1871 Bastardy Act and the addition of clause 5 to the 1874 Industrial Schools Act; the one could be invoked to enjoin an Aboriginal child’s maintenance on its putative white father, and the other ensured the education of an Aboriginal minor by enabling mission managers to become the child’s lawful guardians. His election as protector of Aboriginal natives in June 1887 was a deserved distinction and it made legal what had long been accepted in practice.

Never content with his empty title of bishop of Port Victoria, Salvado was relieved when it was changed to the titular bishop of Adriana in March 1889. In the work of reclaiming some seven hundred of his uncircumcised Murara-Murara and providing them with a means of living, he finally broke through tribal boundaries and won over to him 101 of the circumcised across the border. He loved them all to the end. After securing the future of his mission, he died in Rome on 29 December 1900, calling his distant piccanninies one by one. His remains were brought to Western Australia in June 1903 and re-buried in the tomb of Carrara marble behind the high altar in the church of his beloved New Norcia.

Select Bibliography

F. Nightingale, Sanitary Statistics of Native Colonial Schools and Hospitals (Lond, 1863)

J. Flood, New Norcia (Lond, 1908)

H. N. Birt, Benedictine Pioneers in Australia, vol 2 (Lond, 1911)

Royal Commission on Condition of the Natives, Report, Parliamentary Papers (Western Australia), 1905 (5), evidence 2021-93

R. Rios, History of New Norcia (Archives, New Norcia)

Salvado papers (Archives, New Norcia).

Citation details

Dom William, ‘Salvado, Rosendo (1814–1900)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/salvado-rosendo-2627/text3635, published first in hardcopy 1967, accessed online 3 November 2015.

This article was first published in hardcopy in Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 2, (MUP), 1967

Link: https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/salvado-rosendo-2627